Woman Word: Anglo-American Women Write the Novel

“Is a pen a metaphorical penis?”

“A writer’s style is all she has and the price of the making of it is everything she has...

She must be well read, she must be clever. She must be curious, she must be sharp.

Whatever she can muster to her fingertips, let her,

and her hands will begin to control the instrument she desires.”

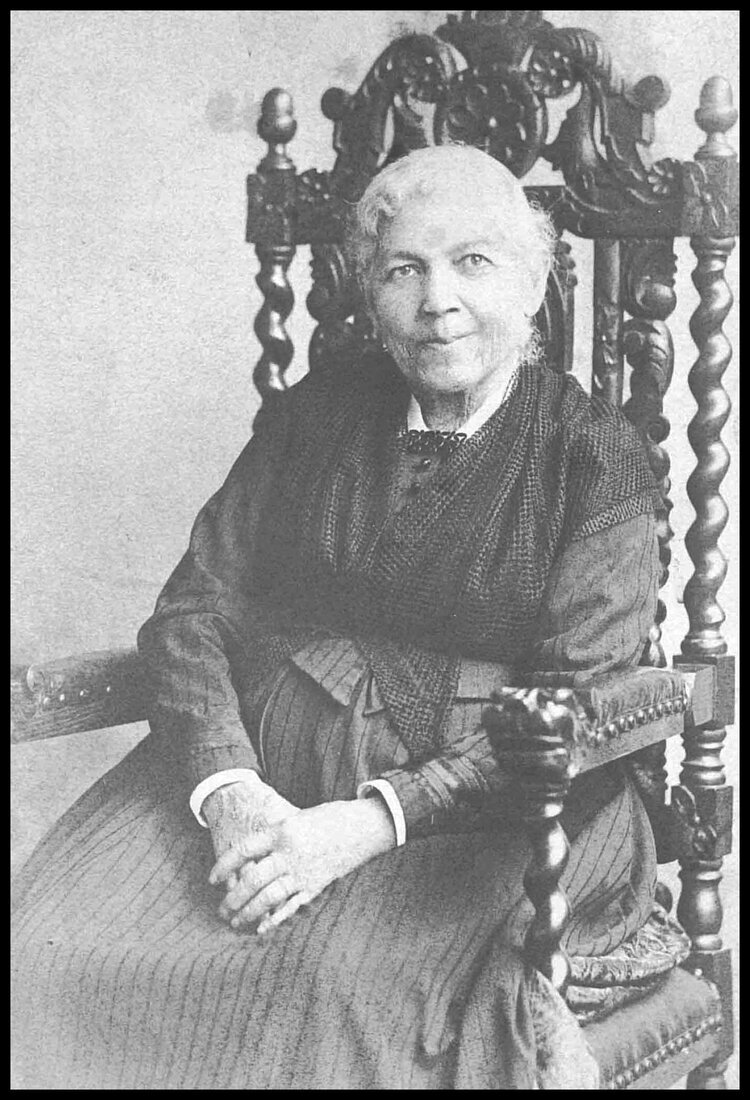

Harriet Jacobs, by C. M. Gilbert, Gilbert Studios. Photograph, 1894.

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar began their revolutionary study of female authorship with the following question: “Is a pen a metaphorical penis?” This course considers both the motivation behind, and the consequence of, Gilbert and Gubar’s self-consciously seminal question by reading and talking about all kinds of novels by Anglo-American women, from Aphra Behn to Jeanette Winterson, Jane Austen to Toni Morrison. Since women have written beautiful poetry, produced successful plays, and shot exquisite films, why focus on the novel? Because the novel is the genre most often associated with “the feminine” in Western literature (even now, 80% of habitual novel-readers are women), and it is the literary form females have written most.

The novel is also deeply creative—elastic and eclectic. It was and is the popular culture of its day (from eighteenth-century Gothic thrillers to contemporary romance novels), and it remains an experimental form, containing most other genres between its covers—including poetry, the essay, travel writing, autobiography, philosophy, scientific inquiry, photography, and film. In addition to examining Anglo-American women’s novels across the 300 years of their publication, this course also asks students to analyze the history of formal literary criticism about women’s writing from Virginia Woolf to Alice Walker to J. Jack Halberstam and to view such criticism as creative texts in and of themselves—texts that are often fantastical and highly subjective. Thus, students should expect to read a good bit of literary criticism as well as upwards of ten novels, watch at least one film, and be ready to produce their own “woman words.” The final course project is the production of an anthology of Woman Word, authored by the students themselves.

Woman Word students attend a poetry reading with legendary feminist literary critic Sandra Gilbert at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC., December 2017.

Woman Word students stand next to a life-sized portrait of novelist, essayist, critic, and Nobel-prize-winning author Toni Morrison, painted by Robert McCurdy and held at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC.